A Comprehensive Master Plan for a Fifth Gate at Walt Disney World

This article presents a comprehensive planning framework for a potential fifth theme park at Walt Disney World, drawing on district planning documents, land suitability analysis & modern park design

Please consider subscribing or buying me a coffee.

Apologies for the delay from my last article, I decided on New Years Day to write a six episode limited series Screenplay, 245 pages and 3 drafts later, I finally had time to finish this article. Enjoy..

Right before Universal opened Epic Universe, the President and COO of Universal Orlando Resort said the following:

“This is such a pivotal moment for our destination, and we’re thrilled to welcome guests to Epic Universe next year. With the addition of this spectacular new theme park, our guests will embark on an unforgettable vacation experience with a week’s worth of thrills that will be nothing short of epic. Our Universe will never be the same.”

That line matters more than it might seem. Universal wasn’t just opening a new park - it’s explicitly signalling an ambition to turn Universal Orlando into a seven-day destination, not a two- or three-day stop. In a previous article, I argued that Universal is unlikely to take its foot off the gas until it reaches that goal, even if that ultimately means adding a fourth theme park next to Epic Universe sooner rather than later.

Walt Disney World, meanwhile, is dealing with a very different problem.

I’ve already written about Magic Kingdom’s capacity issues, but it would be disingenuous to pretend the other three parks aren’t facing similar - and in some cases worse - pressure. Anyone claiming the Disney World guest experience is the same as it was 5, 10, or 15 years ago simply hasn’t spent meaningful time in the parks. Objectively (and diplomatically), Disney World is a victim of its own success. The resort attracts an enormous number of visitors, and increasingly that volume comes at the expense of experience.

Disney is clearly aware of this and has begun addressing it through incremental additions and targeted investments. The open question is whether that approach is enough to prevent a familiar sequence of problems:

-Capacity stress becoming more visible

-Length of stay stalling, particularly as Universal’s continues to grow

-Pricing alone no longer doing the heavy lifting

Historically, Disney hasn’t waited around to find out. Stagnation is what truly worries Disney management — not collapse, but the kind of slow growth erosion that can’t be explained away by external factors. There are early signs of this today. Disney World isn’t haemorrhaging visitors, but TEA attendance figures show growth is slowing.

Which leads to a legitimate internal question Disney may already be asking:

Has the resort reached the point where another gate is the most efficient way to manage demand and revenue growth?

Disney has access to extraordinary amounts of data: guest surveys, competitive benchmarking, length-of-stay analysis, and direct comparisons with Universal just down the road. It’s entirely plausible that those signals point toward an uncomfortable conclusion - that new rides alone aren’t enough, and that the resort may eventually need a fundamentally different offering rather than continued iteration on the four parks it already has.

Disney fans all have opinions on a fifth gate. I’m not here to argue for or against one emotionally. The data will do that arguing on its own. What is worth stating clearly, however, is that Disney effectively already has regulatory approval to build another theme park any time it chooses between now and 2045 - a striking contrast to the years-long planning battles Universal has faced elsewhere.

What follows is not an argument that Disney should build a fifth gate, but a case study in viability: design principles, location, scale, and the kinds of problems a modern Disney park would need to solve. The last Disney World theme park opened 28 years ago. The industry- and guest expectations - have moved on.

I won’t be discussing IP. In this hypothetical, the park only fulfils one thematic requirement: it must be meaningfully different from the four that already exist. Everything else is left deliberately blank.

Where a fifth gate could actually go

Before talking about design, viability, or what a new park might solve, the first constraint is brutally simple: where could it realistically sit?

Walt Disney World spans roughly 28,000 acres, but that headline number is misleading. Once you strip away conservation land, buffers, waterways, utilities, road corridors, and undevelopable parcels, the picture tightens quickly. More importantly, Disney’s four existing theme parks already occupy a far smaller operational core — roughly a 7,500-acre box that contains Magic Kingdom, EPCOT, Disney’s Hollywood Studios, and Disney’s Animal Kingdom.

Within that core, three of the four parks — EPCOT, Hollywood Studios, and Animal Kingdom — sit relatively close together, no more than two miles apart. Magic Kingdom is the outlier, located several miles north of the others and functionally separated by both geography and infrastructure.

That matters, because Disney World doesn’t operate as four isolated parks. It functions as a networked system: shared roads, shared utilities, shared transport, shared hotels, and shared guest behaviour patterns. Logistically, it would make little sense to push a new park further away from that system when so much of Disney’s operational efficiency comes from proximity.

If anything, the opposite logic applies. A fifth gate that bridges the gap between Magic Kingdom and the southern cluster would act as an infrastructural stepping stone — tightening the resort’s footprint rather than stretching it further. That kind of placement simplifies transport planning, reduces duplication, and improves resilience across the system.

Then there’s the final constraint that cuts through everything else: land suitability. When you overlay Disney’s property with environmental and development suitability data, the majority of the land simply isn’t viable for large-scale construction. Wetlands, flood-prone areas, protected zones, and fragmented parcels eliminate huge swathes of the map immediately.

So the approach to identifying a location for a new park becomes surprisingly narrow and methodical:

Stay within roughly two miles of at least one -ideally two- existing parks

Identify a large, contiguous parcel with a high concentration of “suitable” or “slightly suitable” land

Only then begin triaging secondary factors:

- access to existing arterial roads

- proximity to resort hotel clusters

- likely guest movement patterns

-and the cheapest, most scalable transport solution required to connect it all

At that point, the conversation stops being speculative and starts becoming practical. The map does most of the arguing for you — and it rules out far more options than it enables.

Before showing the results of the land-suitability analysis, it’s worth addressing the locations that often feel logical when a fifth gate is raised, but tend to fall apart once they’re tested properly.

I posed the question on Twitter to get a sense of where people instinctively feel a new park should go, and the responses were thoughtful and predictable in equal measure.(great minds!)

Several people suggested repurposing land around EPCOT, particularly reimagining parts of the existing parking area. It’s true that EPCOT appears, at a glance, to have a lot of space. However, once you account for embedded infrastructure, circulation, and how that land actually functions today, the conversation becomes more complicated. The short version is that while change may be technically possible, it immediately raises a more important question — whether there’s a better solution elsewhere. We’ll come back to that.

Others pointed north or west of EPCOT. Again, these are answers that make intuitive sense when looking at a resort map, but the reasons they struggle become clearer once the land-use and suitability data is introduced.

One suggestion I personally liked — and one that has influenced my thinking more than most — was the idea of utilising the Transportation and Ticket Center parking area, which spans roughly 150 acres. On paper, it’s an attractive idea: large, central, and already integrated into the resort’s transport network. But here too, the short answer is that there are alternatives that preserve the value of that existing infrastructure rather than replacing it.

The important takeaway isn’t that these ideas are bad. It’s that intuition alone isn’t enough. Once land suitability is treated as a hard constraint rather than a secondary consideration, many of the most obvious answers quickly lose viability.

And more interestingly, once that same filter is applied consistently across the resort, a much smaller set of options begins to emerge — three in particular — with one location that becomes increasingly difficult to ignore.

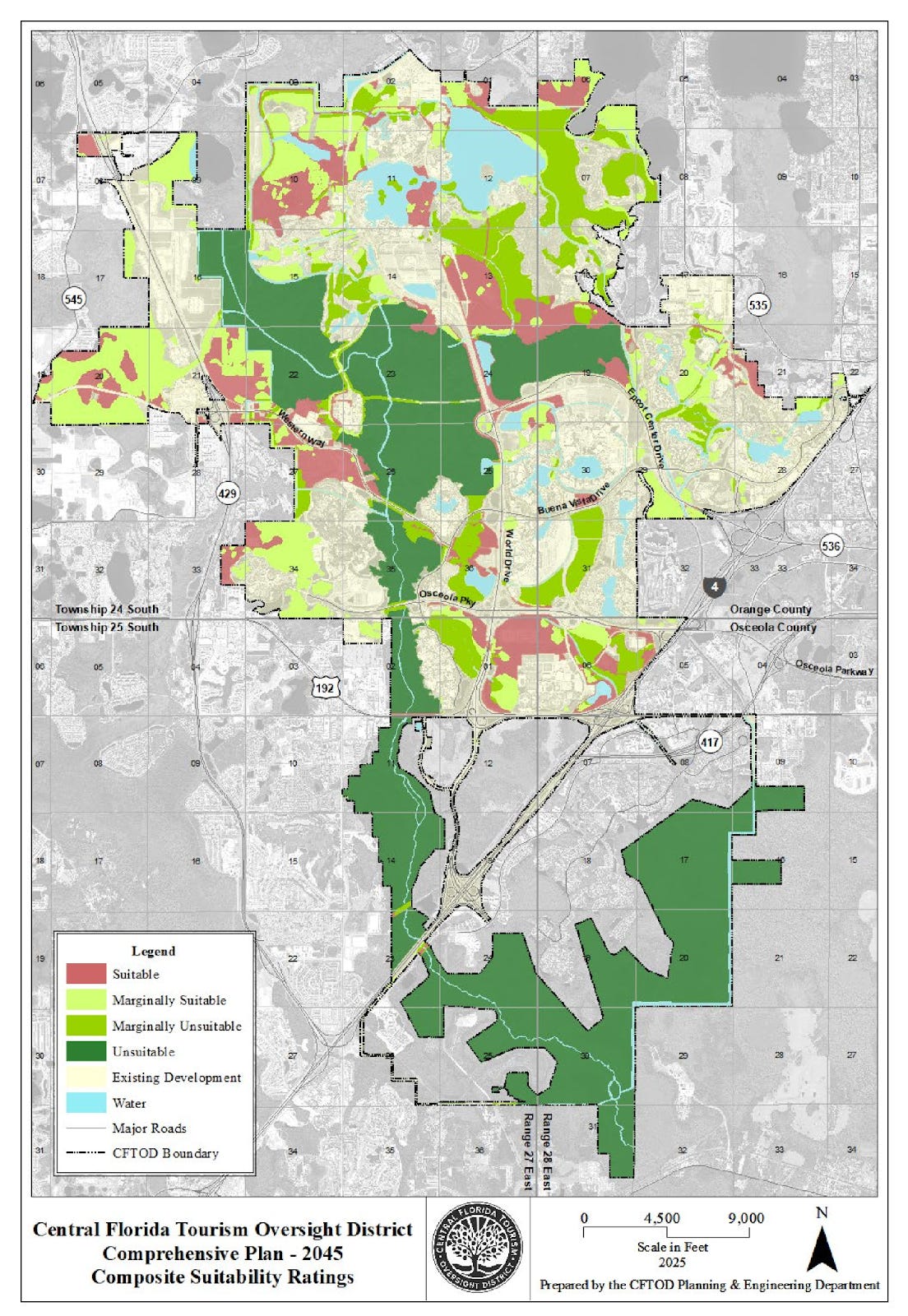

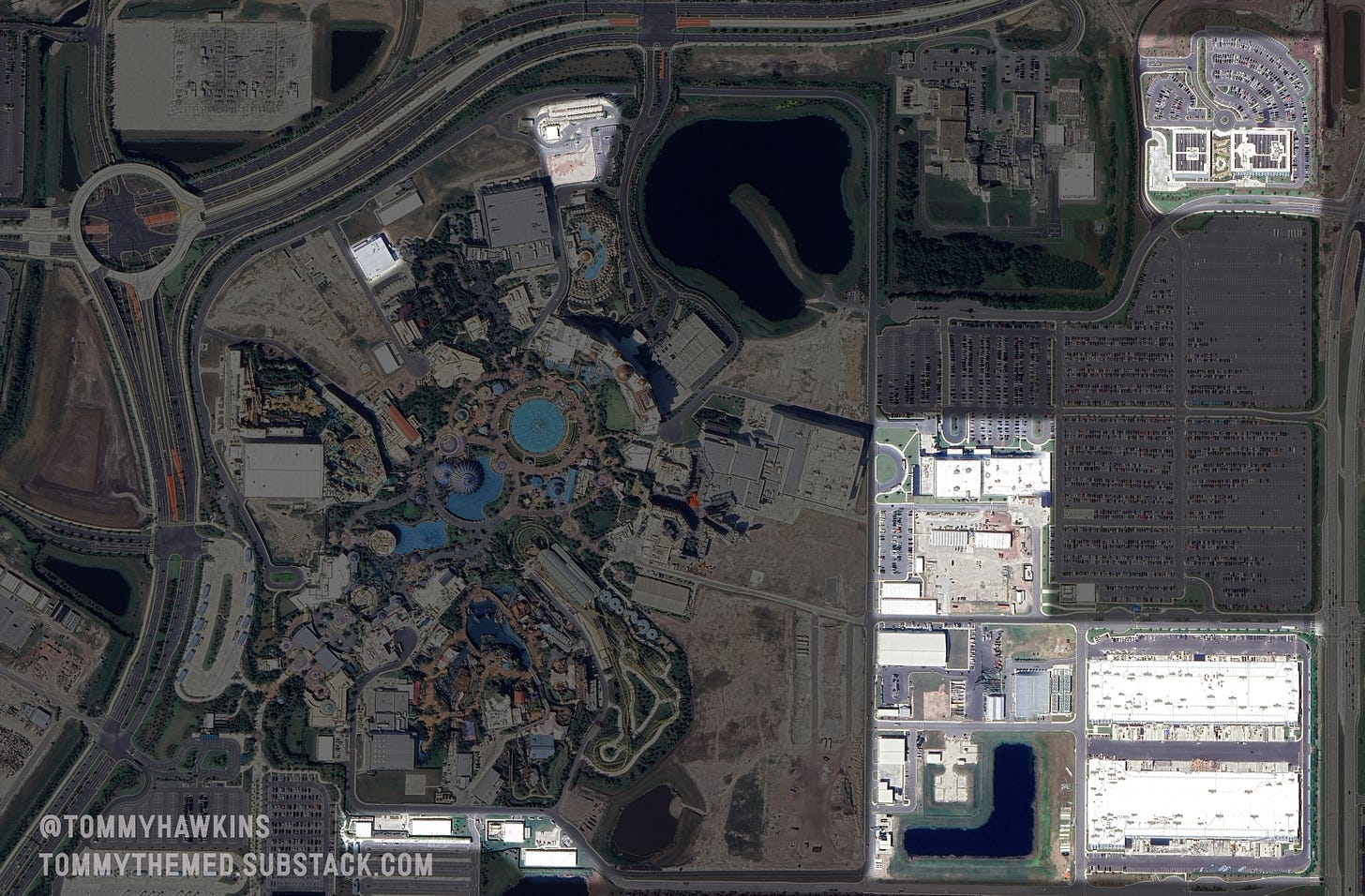

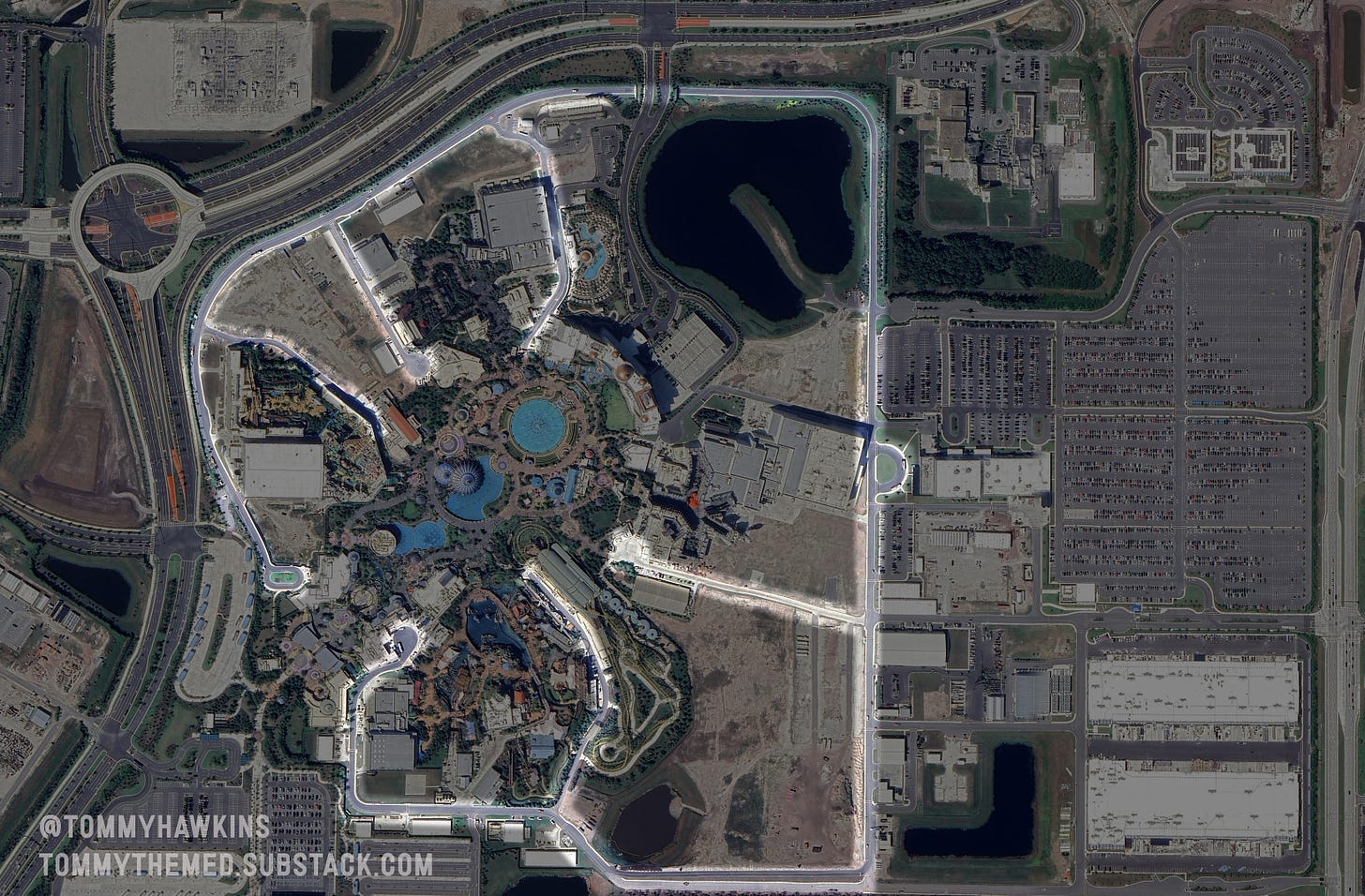

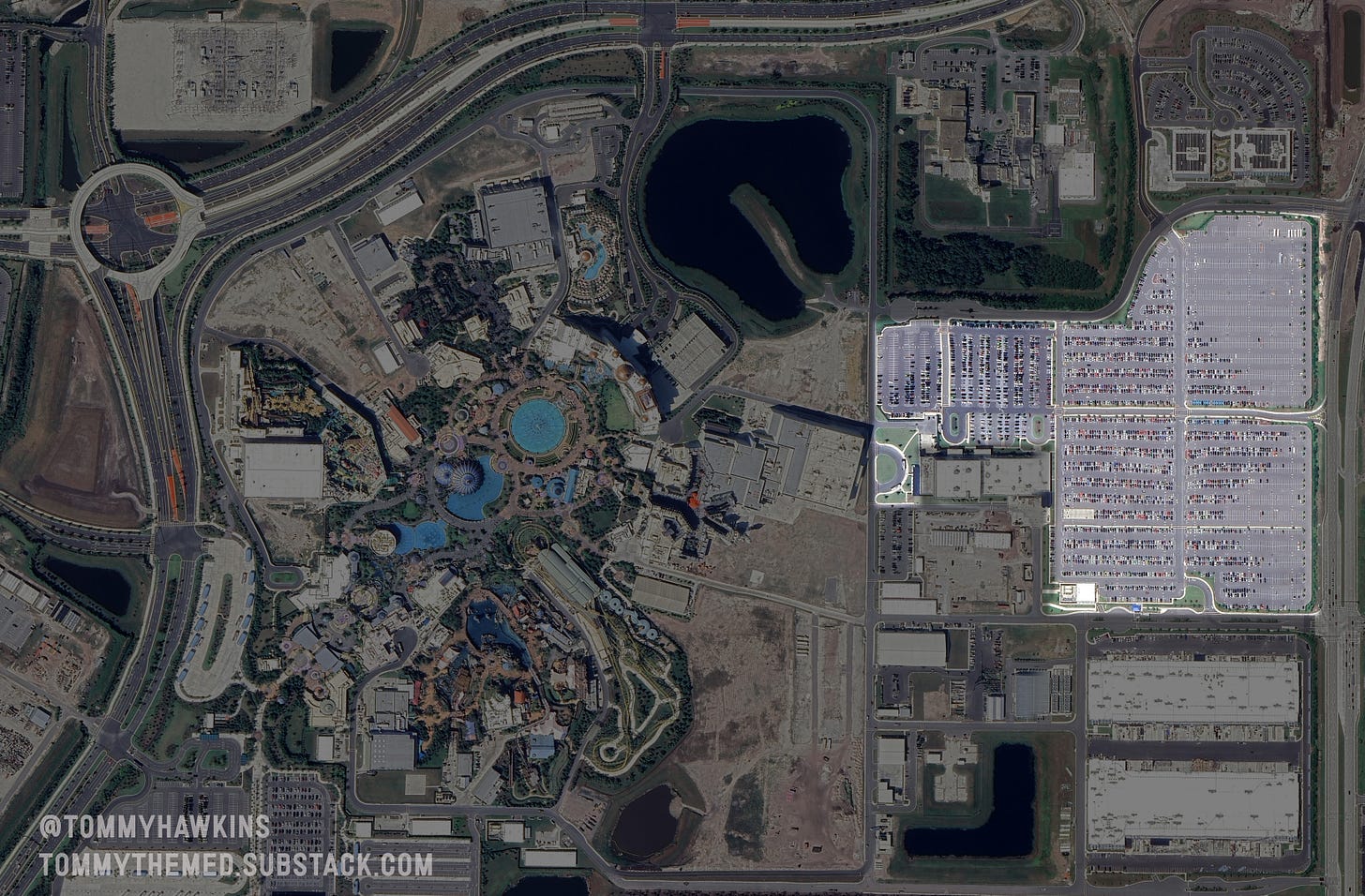

Here is the land suitability map for Disney World:

When focusing on only the land assessed by the District’s suitability classifications around 40% of the evaluated land is deemed unsuitable for development.

When combining the District’s “Unsuitable” and “Marginally Unsuitable” classifications - around 60% of the evaluated land is effectively constrained against major development. Before I consider infrastructure, proximity, or operational logic, the majority of the land has already been filtered out.

Focussing on the remaining 40% of land that is labelled Suitable or marginally Suitable, we have multiple locations we can triage.

The first location is a very large parcel of land, around 250 acres, attached to ESPN world of Sports, I would argue there is nothing wrong with this location, it is close to a few of the parks, but it is 5 miles from Magic Kingdom. The intention of this is to bring these parks closer together rather than spread their footprint. It also raises the question, what other things could be built here that are more suitable to ESPN World of Sports, be that more resorts or other unknown attraction that supports what already exists?

The next location somewhat addresses a suggestion made to me on Twitter, building the park directly north of Epcot.

Despite there being SOME land that that fits our category, it is not enough acreage and it is spread along Vista Boulevard, with a large swathe of unsuitable land blocking a natural land bridge between the two parks.

Now attention turns to the three serious contenders.

The first is the large contiguous parcel of land, at 300 acres, the parcel sits at the intersection of Western Way & 429 highway. It has a lot of positive attributes, the only mark against it is that it is the furthest away from all 4 park and resort hotels, and would only spread the entire resort further apart as it is more than 2 miles from every other theme park.

Remember we are interested in seeing as much red as we can, pale green is also viable.

The second parcel, and in my opinion a very strong contender, is a 300 acre parcel of land West of Grand Flo. Floridan Way is in process of being upgraded and re-routed and touches this parcel. If you are looking for a sign this could be the place, that could be it.

The only thing I feel goes against this parcel is although it somewhat balances the north south divide of parks, it does nothing to connect the dots between existing parks as it is located further west of MK. Also some of this 300 acre parcel is already being utilised for drainage ponds for Rivers of America removal, so there may be logistical problems with sharing a drainage basin and infrastructure we are not fully seeing yet.

The final location is so obvious that many would kick themselves that they didnt think of it earlier. There is also some extremely historical providence that I will come back to later, and only remembered after I went through this process.

The Parcel is “only” 200 acres, but being bisected by Vista Boulevard means its actual two parcels of 145acres and 55 acre acres south. It is actually the site of Walt’s Runway - but thats only part of the historical connection.

The Parcel is directly east of TTC, the Monorail runs in a nearly straight line along its western edge, it attaches directly to Floridian way and World Drive - do you see where I am going with this?

This location also benefits from the proximity to the rejected Vista bld parcel - I will come back to that.

Addressing the location in relation to the other parks. The parcel is 1.5 miles from Magic Kingdom, directly in between that park and Epcot, which is less than two miles south east. Essentially this park plugs the gap between the southern parks and Magic Kingdom. When you look at this parcel on a map, it seems to be the centre of the Disney World Universe.

There’s more, this site has always been good for something. An aerial photo by Bioreconstruct reminded me that I did an overlay several years ago placing the original 1967 master plan of the E.P.C.O.T onto modern day Disney World . This parcel sits where the original EPCOT was intended to be built.

For the purpose of this Article, I am declaring this plot of land the winner, it ticks many logistical boxes, its the only one that meets all criteria, and has very few downsides that I can think of. This is the candidate I will take forward to design stages.

Design principles for a fifth gate

Before revealing what this park looks like, it’s important to be explicit about what it is trying to do — and just as importantly, what it is not.

This is not an exercise in IP placement, ride wish-lists, or nostalgia. It’s a blank-page master-planning problem. The goal is to design a park that could operate, expand, and evolve for decades without needing the kind of retroactive fixes that increasingly define the existing Disney World parks — favouring a measure multiple times, build once philosophy over the more reactive, iterative approach Disney has often taken.

To do that, the design criteria need to address three things simultaneously:

- what currently doesn’t work at Disney World,

- what modern theme parks like Epic Universe get right,

- and where those modern designs can be improved further.

It’s often said that Walt Disney Imagineering never threw ideas away, only put them back in a drawer for another day. I’ve seen former Imagineers argue that we should look to Walt’s original Disneyland plans when thinking about a fifth gate at Walt Disney World. I’m not convinced that’s the right place to start.

This exercise is about creating something fundamentally new. There’s a real danger in treating the ideas of one individual -even Walt Disney- as scripture. Those plans were a snapshot of a specific time and place over 70 years ago. It’s worth asking whether a futurist and visionary would really be comfortable with a company endlessly looking backward rather than forward.

Disney exceptionalism shouldn’t mean “if it isn’t broken, don’t fix it.”

What has historically made Disney exceptional is its ability to deliver something better than anyone else attempting the same thing. One could argue that Universal has reached parity over the past two decades. Staying ahead doesn’t come from creating museums - it comes from continually rethinking how things should be done, just as the company’s founder did.

What this park is trying to fix

The biggest structural problem across Disney World today isn’t any single attraction - it’s the reality of being forced to retrofit design decisions made over the past 55 years.

The state of play at Disney World looks something like this:

- The parks were never designed to accommodate the sustained crowd levels they now attract, forcing constant compromise in both design decisions and guest experience.

- Expansion frequently requires demolition, disrupting parks that continue to operate while welcoming tens of millions of visitors each year. Construction walls have become the norm rather than the exception.

- New attractions are often inserted into spaces never designed to absorb them, creating knock-on issues with circulation, sightlines, and capacity elsewhere in the park.

The recurring theme running through all of this is compromise.

Guest experience becomes a compromise. Design intent becomes a compromise as construction complexity eats into budgets simply to make things fit. Capacity becomes a compromise every time a major attraction shuts for years to be replaced - often with little or no net gain when it reopens.

This creates a cycle where every improvement introduces new friction somewhere else.

The intent of my fifth gate is to break that cycle entirely.

When studying the existing Disney World parks, it’s often possible to see exactly where short-term design decisions were made — and how those decisions continue to shape the guest experience decades later.

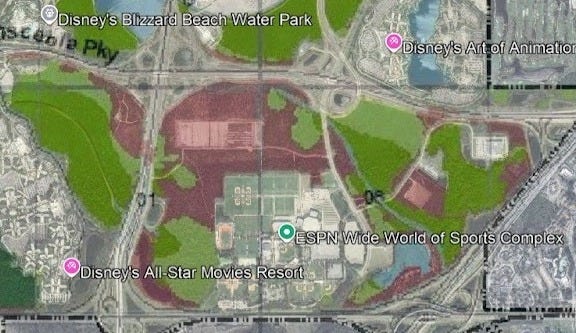

A clear example is Disney’s Hollywood Studios, originally Disney–MGM Studios. As documented in books like Jay Bangs by Sam Greenaway- the account is the following: Michael Eisner (whilst working at Paramount) was well aware of Universal’s plans to build a behind-the-scenes studio tour in Orlando and moved quickly to ensure Disney had a competitive response. The result was a park designed not just as a theme park, but as a functioning production studio, complete with office space, operational facilities, and employees commuting daily to work in non-guest-facing roles.

Indicative map of MGM, showing footprint versus attractions/guest occupied areas.

That decision made sense in its moment. It was a business response, not a master-planning exercise.

Fast forward nearly four decades, and the consequences are hard to ignore. After years of hurried expansion to complete what opened in 1989 as an intentionally incomplete park, Disney’s Hollywood Studios now operates with a substantial portion of its footprint locked into back-of-house functions, offices, and Cast Member parking. Expansion options are constrained, circulation is uncomfortable at peak periods, and the guest experience is shaped as much by what the park has to work around as by what it adds.

This isn’t a critique of the designers who inherited those decisions - if anything, it’s hard not to sympathise with anyone asked to solve a problem created decades earlier. It’s a reminder that when non-theme-park functions are allowed to take precedence over the guest experience, the consequences can last for generations - and that putting the guest at the centre of every design decision from day one isn’t idealism, it’s self-preservation.

One way Epic Universe addresses this is by designing the park as what I’d describe as guest space only, with back-of-house and other non-essential functions moved outside the park boundary rather than embedded within it — meaning that everything built inside the park exists to serve the guest directly, not the operation.

That principle isn’t abstract. It has very real implications for how a park is laid out, accessed, operated, and allowed to grow.

What Disney can learn from Epic Universe’s design strategy?

Epic Universe is not the perfect park, at least not today. I have covered many aspects in previous articles, and this article is not here to re-litigate what improvements need to be made.

The fact is that since Disney last opened a Theme Park in 2016 (Shanghai), Universal have designed and built a themed Water Park (Volcano Bay 2017), Universal Studios Beijing (2021), Epic Universe (2025), have Universal Kids Texas (2026) and Universal Great Britain (2031) resort both under construction right now. With a conveyor built of design projects, Universal Creative have been able to refine design aspects that work for Theme Parks. It can be debated whether Universal set the trend or merely stayed ahead of the curve with highly immersive themed lands - but they took that concept and ran with it at Epic Universe - many argue that they do not like this idea and that Theme Parks should not be built like this, the counter to that argument would be to look at visitor number data since 2010 when Hogsmeade opened at UOR, it appears that lots of people love this concept.

Whether Theme Park fans like it or not, themed immersive lands are here to stay for the foreseeable future, so it would make sense to consider the best ways Disney could act to deliver that in a new park - Universal have settled on a method to encapsulate guests.

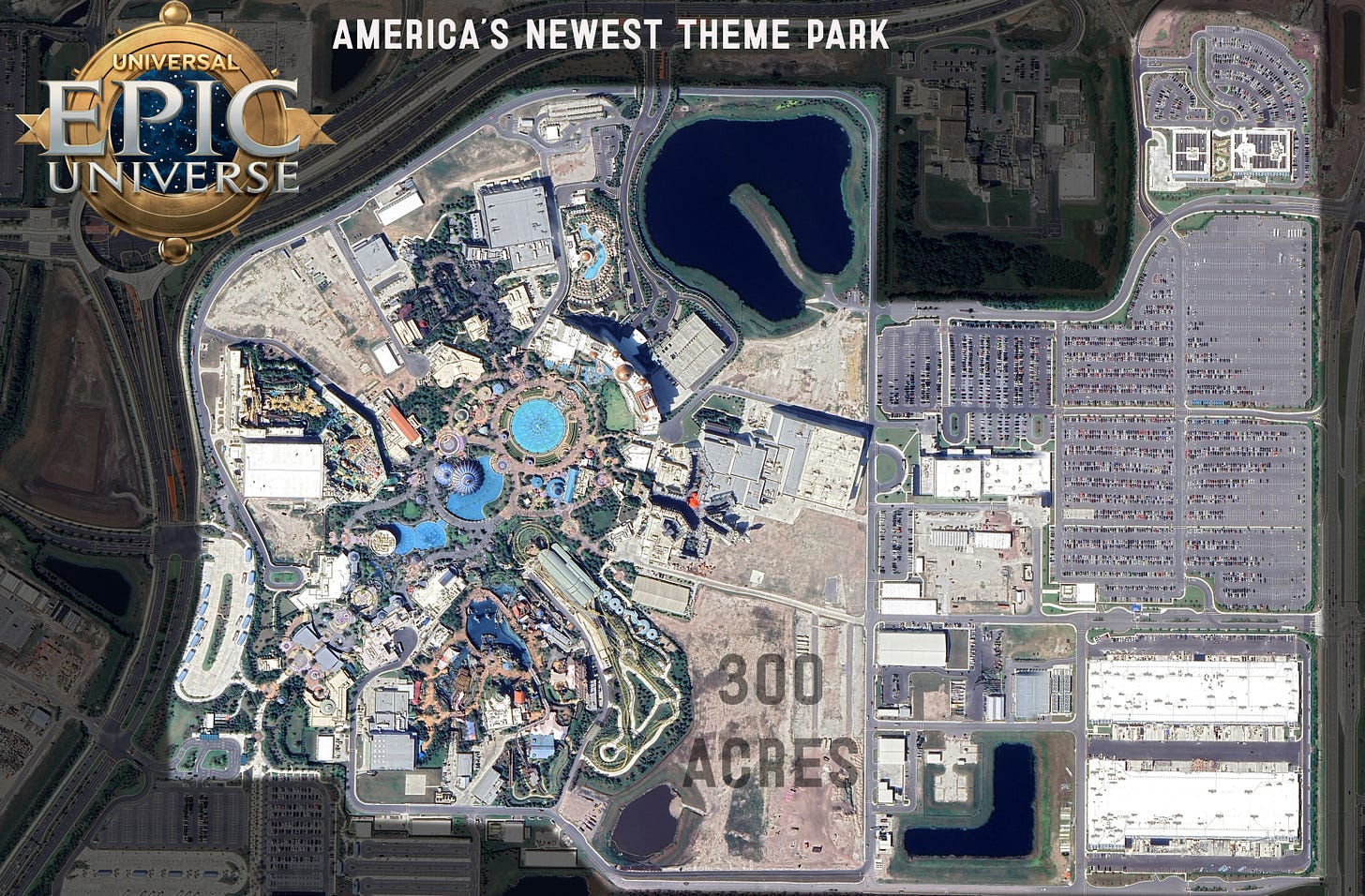

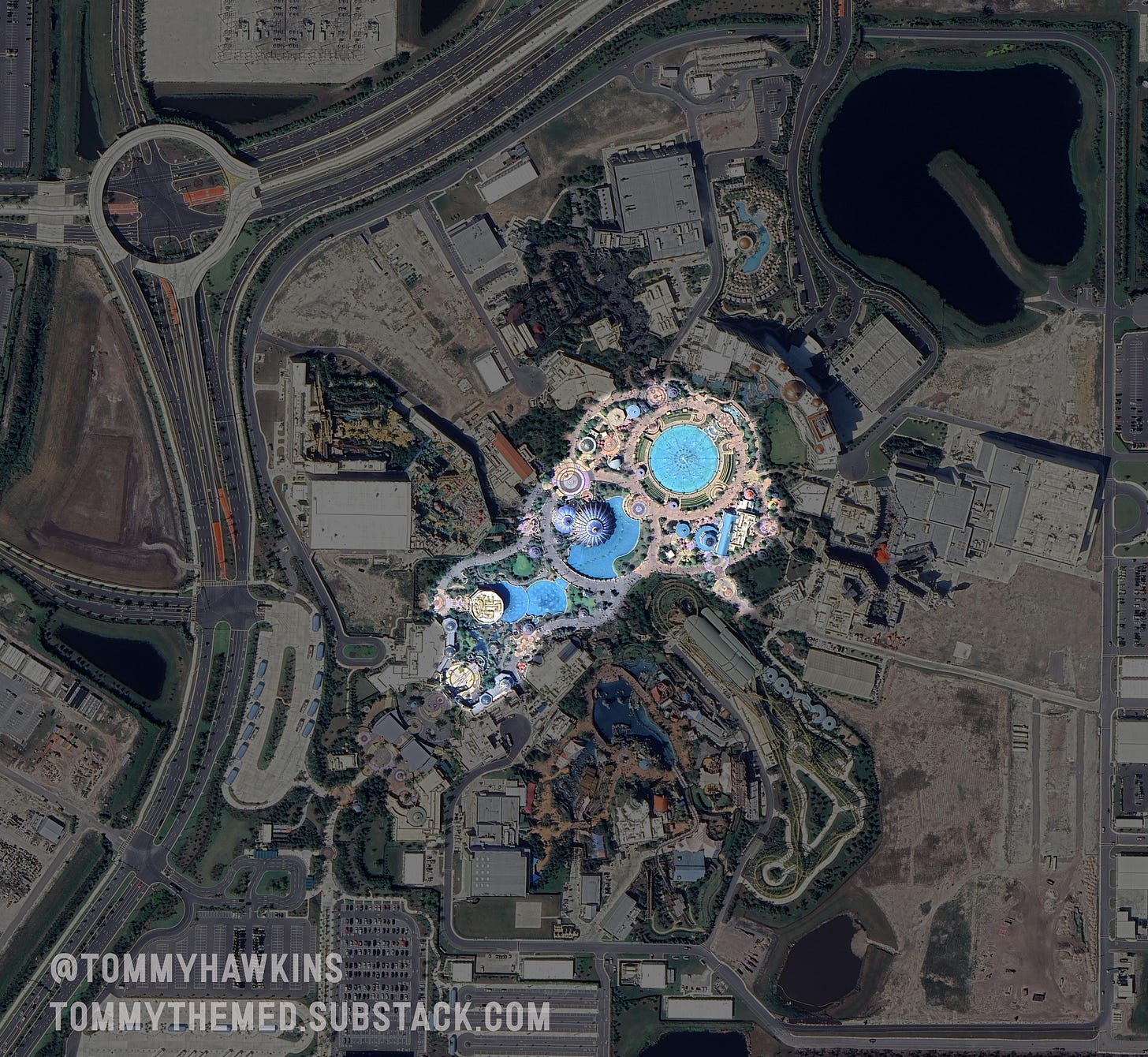

One of Epic Universe’s most important design decisions is also one of its least discussed: back-of-house infrastructure is largely removed from the guest-facing park entirely.

Epic is the first modern theme park to centralise major back-of-house functions — logistics, maintenance, costuming, warehousing, and operations - within a separate, purpose-built campus outside the park’s ring road, rather than threading those functions through guest space. That single decision eliminates many of the compromises that have defined earlier Disney and Universal parks.

This design takes that principle as a starting point, not an exception.

A guest-only park, taken to its logical conclusion

Building on Epic’s approach, this fifth gate is conceived from day one as a fully guest-only park envelope - meaning that everything built within the park exists to serve the guest directly, not the operation.

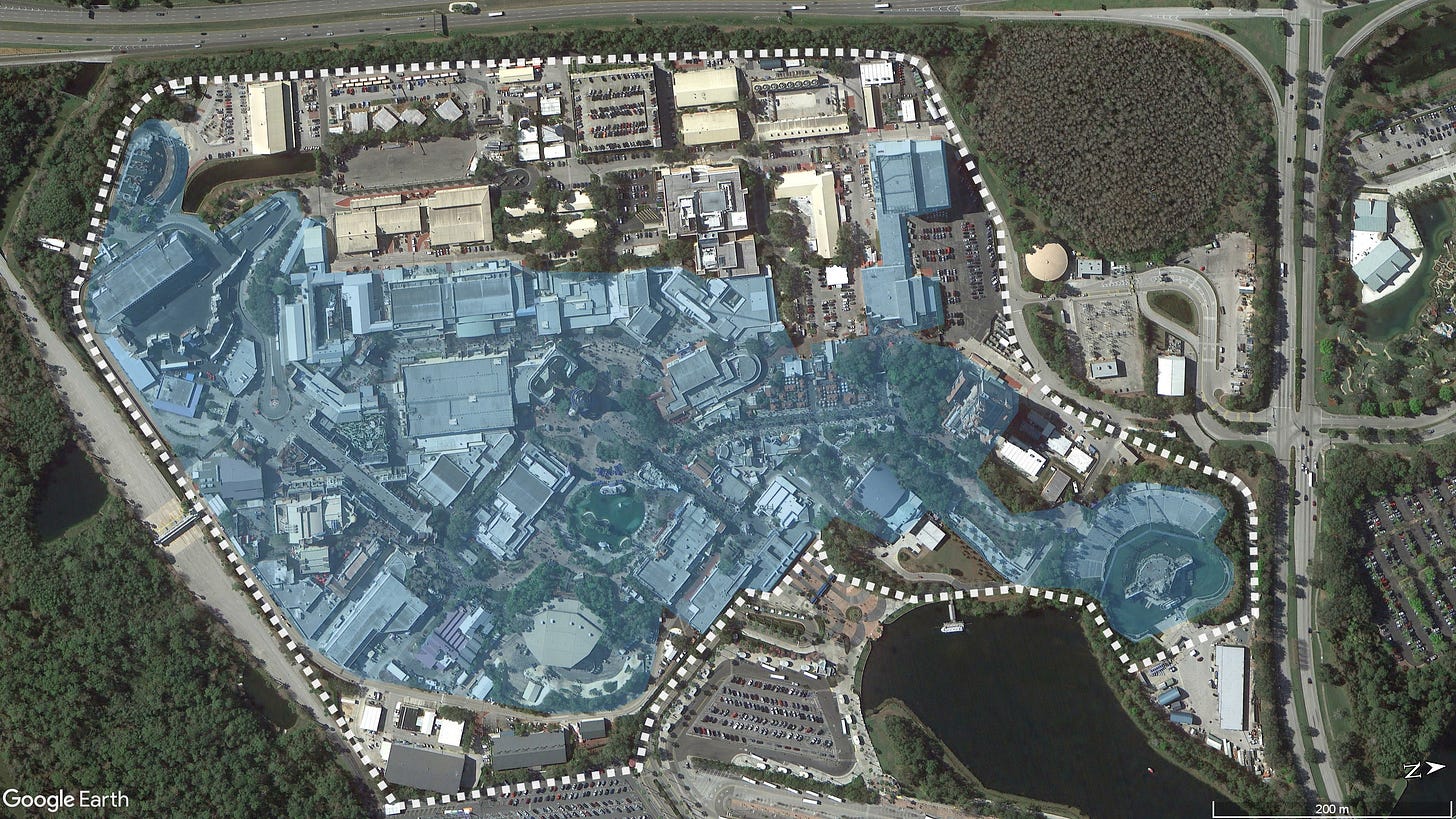

Overview of Epic Universe, the current footprint for the park is around 300 Acres.

To achieve that, several design criteria are locked in from the outset:

All primary back-of-house functions are located outside the park boundary, allowing guest-facing land to remain uninterrupted and expandable over time. Back of House is incorporated in area covering around 120 acres. It is worth noting that these buildings are large enough to cover logistics for all three Universal parks, and expandable to cover a 4th Park next door to Epic Universe.

A continuous service ring road sits behind major show buildings, providing discreet access for deliveries, maintenance, and emergency response, while ensuring that no land within the park is consumed by service routes.

Show buildings are designed to back directly onto this service road, enabling efficient access without cutting through themed space — a principle that reduces disruption both day-to-day and during future expansion.

Photo by Bioreconstruct

Team Member circulation is handled independently of guest circulation, with dedicated shuttle routes operating along the service perimeter in much the same way the utilidor system functions at Magic Kingdom, but without requiring below-ground infrastructure. A shuttle bus stop is seen behind Dark Universe:

Team Member parking is located close to the park but outside the themed envelope, ensuring accessibility without sacrificing valuable guest-facing land or creating visual intrusion. Universal has the ability to convert this flat lot into multi-story parking to give way for more BOH.

A central hub is sized deliberately to absorb large crowd volumes, accommodating parades, night-time spectaculars, and peak circulation moments without forcing bottlenecks or relying on temporary crowd-control measures.

Multiple entrances and exits are integrated into the master plan, improving end-of-night dispersion and offering flexibility for hotel guests, special events, and future resort integration — building on lessons learned from Epic’s Helios entrance rather than treating it as an exception.

Fireworks and drone launch zones are planned from day one, with safety envelopes, sightlines, and guest viewing areas designed into the park layout rather than retrofitted later, ensuring compliance without compromising spectacle.

The opportunity here isn’t just improved immersion — it’s long-term resilience. By separating guest space from non-guest functions and planning circulation, access, and spectacle infrastructure up front, the park can grow and change without ever reclaiming space that should have belonged to the guest in the first place.

Epic demonstrates that this approach works. This design applies it deliberately, holistically, and with the expectation that the park will still be evolving decades from now.

What could Disney do to improve and evolve on the Epic Universe Design Blueprint?

1- Internal Expansion within lands -

I wrote about the way Epic had both internal expansion plots baked into existing lands as well additional segments of the “orange” ready to go for the future. I even spoke at length in my last article about Epic’s “Megaplot” a large 21 acre land - large enough for two individual lands.

With the exception of the Megaplot, although none of these larges are small - most being able to accommodate at least 1 new attraction. Universal are still somewhat restricted by those relatively small plots.

An example of this problem could be the following:

How to Train Your Dragon Isle of Berk - is already the largest land in Epic Universe with approximately 13 acres of guest space. It does however have the smallest internal expansion pad - 1.25 acres. Now I was able to provide some insight into what they could build HERE.

However, consider this- How To Train Your Dragon (2025) made nearly $700M at the Box Office, they already had a sequel planned. It is one of Universal’s most successful franchises, and looks to gain a whole new generation of fans - so what if the demand for this IP goes up?

They could build something like I suggested, and the audience still want more, especially in further live action spin offs occur. The land has nowhere else to expand, which means finding room elsewhere.

Therefore, my first design improvement would be to ensure every land has a significant expansion pad, ideally 5-7 acres each, This would shift internal expansion design from prescriptive into almost blank sheets of paper.

This design principle accepts you don’t know what the future of your park looks like, you are not creating problems for future Imagineers, you are in fact giving them options.

In a way, and I am unafraid to throw shade with this, this is exactly how Epcot World Showcase works to this day, albeit on a smaller scale. There are at least 4 expansion pads sitting there just waiting for Disney to greenlight a project, and one of those pads could fit an attraction the size of Space Mountain.

2- Acknowledging current Disney Park problems and planning for them

Looking at Magic Kingdom, we know that Happy Ever After is extremely popular, we know it draws large crowds that all figuratively fight for a good viewing spot to see the castle projections and fireworks. We also know that has quaint as Main Street is, it creates a bottleneck as being the single exit from the park.

Epic Universe has solutions to this problems: a large hub and a second park exit to Helios.

They work for Universal, but would not work for Disney World crowds. Celestial park has the ponds which are effectively large stages taking up lots of room and Helios exit is clearly designed for a relatively small number of guests staying at the hotel

The solution would be firstly to ensure the park has a second entrance and exit that is dedicated to guests staying at specific resorts, this would be supported by its own transportation hub, with potential for expanded sky liner stations, buses and bespoke point to point transportation options (don’t be surprised if this topic gets its own article). The principle of no bottle necks would be applied to the entrance/exit of the park too.

The second option would be to build a hub so large, I am talking, at least five times larger that Magic Kingdom’s hub, that it could not only accommodate large crowds comfortably, but serve as staging for a show. Imagine a space where mini shows could wheel in set up during the day. Or even Staging for the night-time show rises from the centre to add show elements. Perhaps even the opposite is true, that structures that provide shade and seating during the day, are packed away into the ground and night-time - switching to a flat open space. The design principle is a flexible space.

Disney would be able to create more restaurant opportunities that Epic has, and the ability to place smaller family friendly attractions into a large hub area and never compromise of guest viewing area.

3- Epic Universe’s guest space only principle

Arguably, this is more about scale than anything else. Epic’s Back of House facilities is 120 acres, separated from the 100+ acres of pure theme park space south.

With essential buildings pushed outside the berm, and large buildings located on the edges, designers could consider designs where sightlines are less of a consideration and are not restricted by unsightly service buildings. This aligns with our blank canvas principle.

A park fit for Disney World Guests

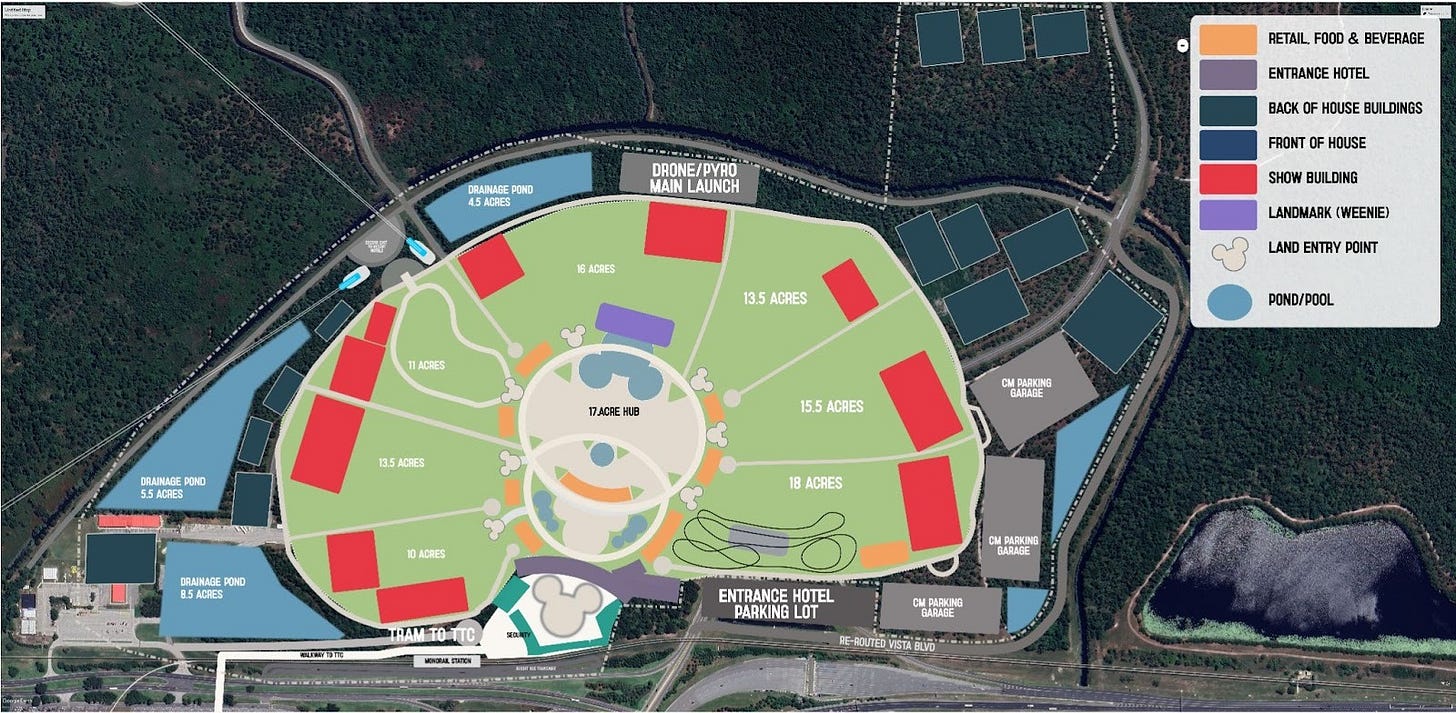

So what did I design?

As always I preface this by saying, what I am about to reveal is conceptual, but viable. We have already established land suitability. I have taken time to consider other practical elements, incorporating all the the design improvements mentioned above.

On the face of it, it looks considerably similar to Epic Universe, however I have taken the time to look at this design process through the lens of a Disney Guest, not simply copy and pasting what Universal do:

Drainage.

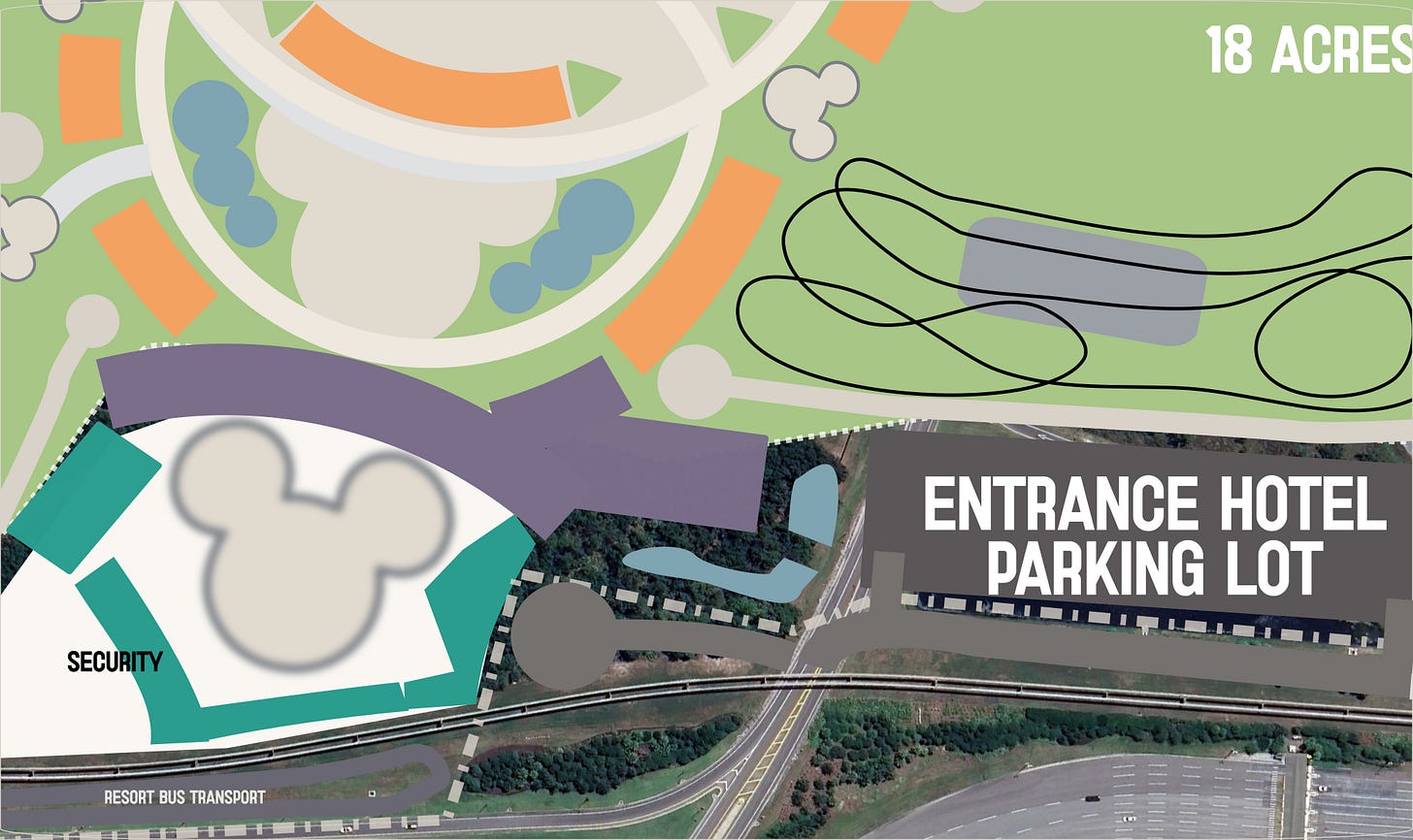

The site is approximately 230 acres. The general principle of this is, if you decide to pave over your site, you must allow a percentage to which the surface run off drains into and slowly drains into the watercourse- usually around 10% of land must remain permeable. I have found suitable locations for 24 acres of drainage ponds

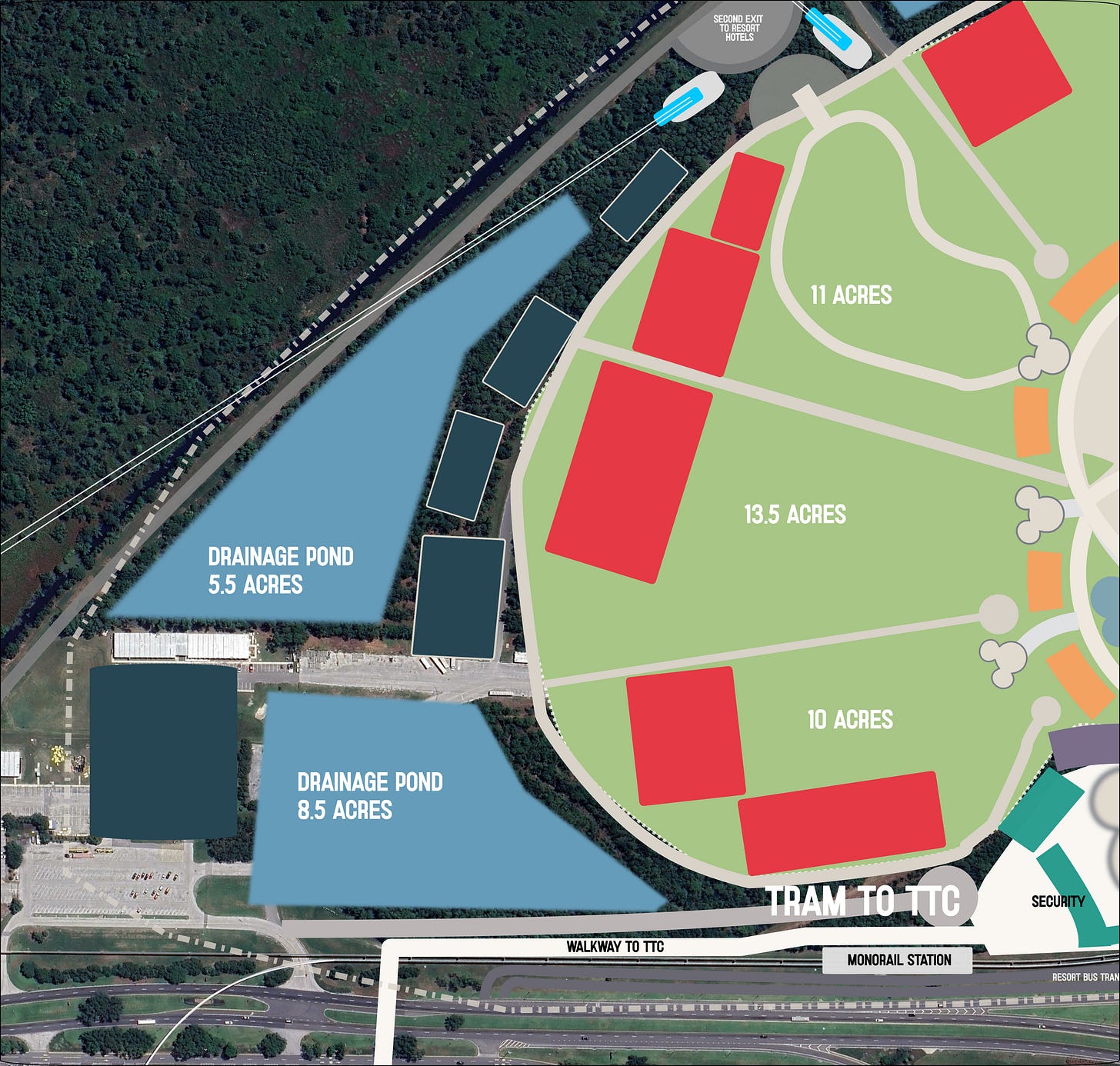

Transport.

The Epcot Monorail runs beside the site, so I therefore built a station to allow a stop. This instantly links three parks in both directions.

Additionally I designed a walking and tram route back to the TTC parking lot. Perhaps the TTC could be upgraded with multi-storey parking to increase capacity. I also found room for bus stops near the monorail station that could serve Resort hotels. This could also be a skyliner station.

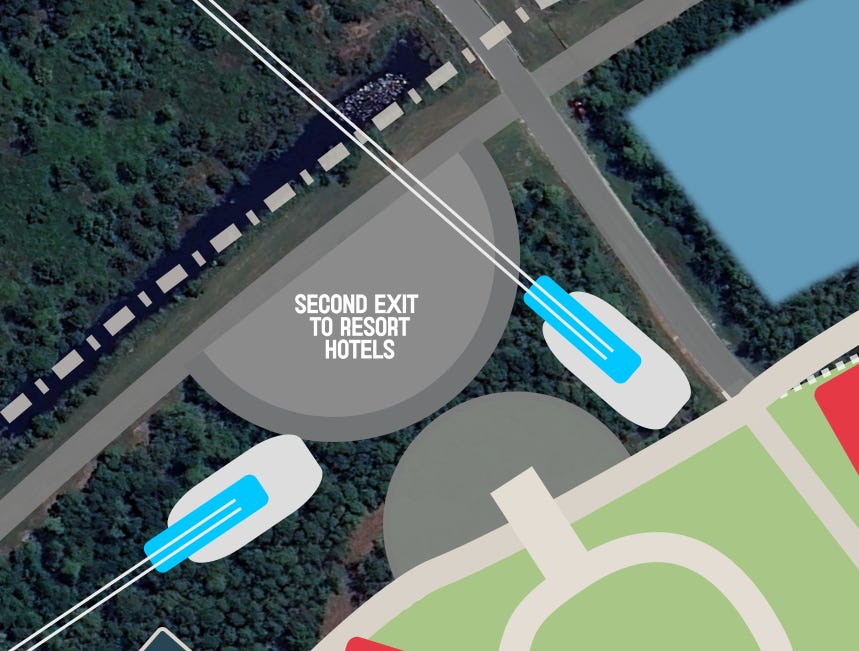

At the Eastern edge of the Theme park, an additional transportation hub exists, in this concept there are two skyliner stations here. One of which could serve as a direct park to park link between this and Magic Kingdom Park.

Creating space to accommodate every type of transport on Disney property, builds capacity, and ability for guests to move around as frictionless as possible.

Back of House - Cast Member support.

I have drawn 13 BOH buildings to demonstrate there is plenty of space to locate these spaces close to the park, but crucially outside the berm. There is additional land available nearby should it be required.

Cast Member parking is also close to the park, but outside the berm too. A ring road encircles the park, with shuttle pick up points next to parking structures. With service builds located along the ring road, there is space for multiple CM rest areas close to the lands in which they work.

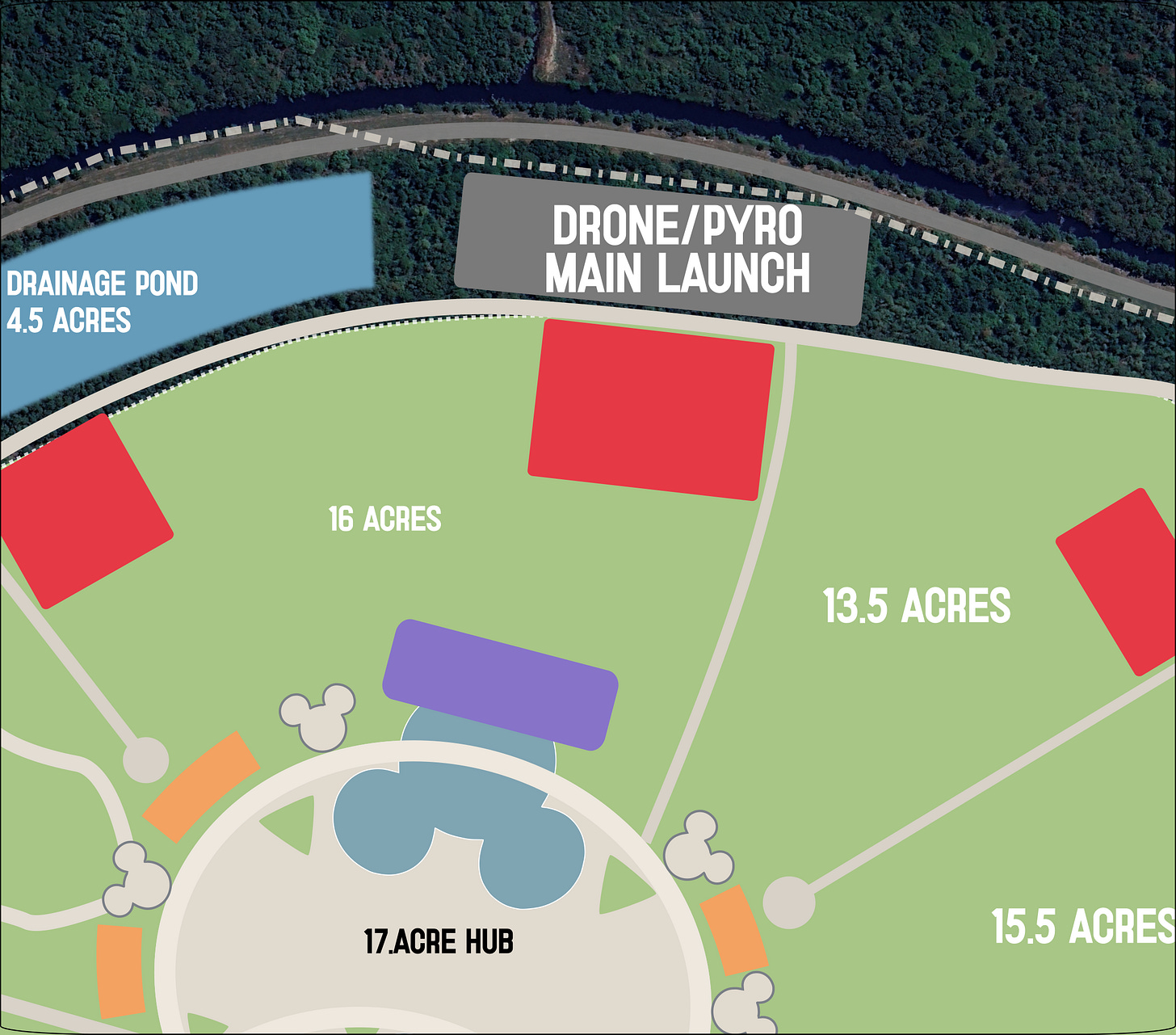

Pyrotechnic and Drone launch.

With this design, I have allocated a 3.5 acre area directly behind the weenie to serve as a drone take off point, which essentially has its own air space, for separation from fire work launches. There is room for smaller pyro launch sites outside the ring road, to further build on Magic Kingdom’s perimeter fireworks shows.

Park Entrance Hotel.

Helios at Epic Universe serves as the backdrop to the park, this is fine, but not very Disney. I followed the trend that both operators have implemented and put a hotel as the park entrance. It is served by its own parking lot. I think we can assume this would be prestige hotel with a high nightly price tag.

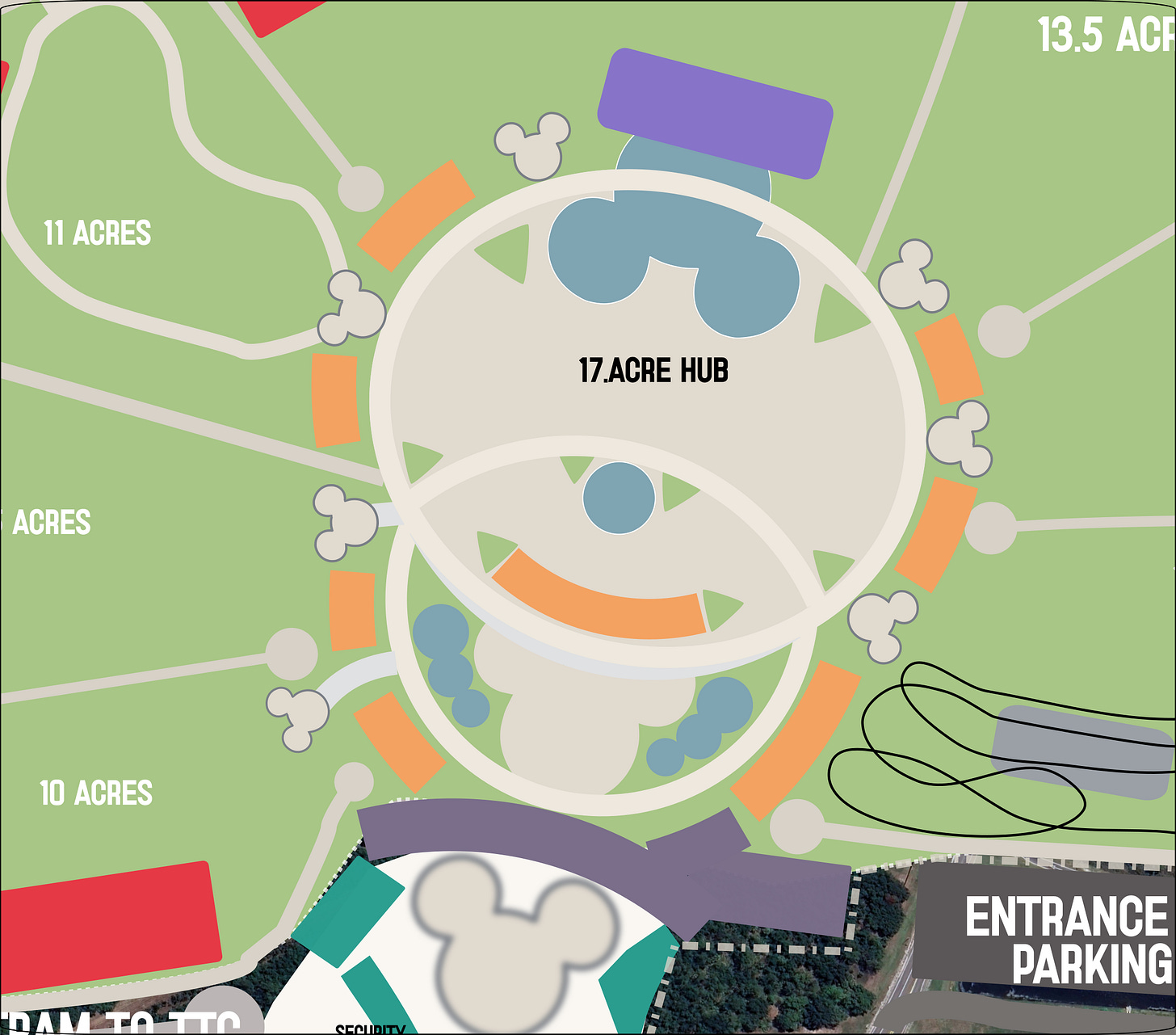

Large Heart of the park.

My design retains the principle of the Hub and Spoke design, but in this design we increase the “axle” size to reduce bottle necks. This area is approximately 22 acres, with around 6 acres as a dedicated standing room, for shows.

Similar to Celestial Park, a Parade road encircles the hub, as do Restaurant spaces. In this design a put a restaurant at the back of the view area to act as a tiered viewing space at night. There is space for parade view as well as smaller attractions - essentially this would act as it’s own land.

Seven lands & a Weenie.

I have segmented the park into seven lands, separated by access roads for fire as well as servicing restaurants and retail in the main hub.

I have placed a weenie at the back of the park. Readers can imagine what that would look like in this park, but it gives guests a main focus point, and a place to project shows onto.

No land is smaller than 11 acres, with the largest being 18 acres. As I set out in my design thesis, in this concept, expansion becomes entirely modular. Not all segments would need to open with the park (like Epic Universe’s 4 lands) or the park could open with seven much smaller lands that grow over time with the theme of that land. Imagine if Star Wars galaxy’s edge had opened with its 14 acres, and had the ability to expand by another 4 acres.

The main takeaway from this is that land is prepped and ready to go from day 1, Disney would only focus their budget on the attraction not the costs attached to compromise as they do currently. It would be a case of converting grass lots or landscaping over to attractions.

I have drawn some show boxes on this mock-up, to give you an idea of scale, the largest ones are bigger than the entire ministry of Magic entry, queue and show building.

This 138 acre theme park would have Epcot’s scale with modern design principles. Ensuring Disney would only have to build it once, and simply add to it, whenever the time was right

Conclusion: building once, properly

None of this is an argument that Disney should build a fifth gate tomorrow.

What this exercise demonstrates is something more restrained - and arguably more important. Disney already has the land. It already has the regulatory freedom. It already has the institutional knowledge. What it hasn’t had, for nearly three decades, is the opportunity to design a new Walt Disney World theme park without inheriting constraints from the past.

Every major issue facing the existing parks today - crowding, circulation, expansion friction, compromised sightlines, back-of-house conflicts — can be traced back to decisions that made sense at the time, but were never designed to scale to the resort Disney World has since become.

A fifth gate is the rare chance to reset that equation.

Not by chasing novelty, IP, or nostalgia, but by applying modern design principles deliberately: separating guest space from non-guest functions, planning infrastructure once instead of repeatedly, allowing lands to grow without demolition, and designing for the reality of modern crowd levels rather than the optimism of a ribbon-cutting day.

Whether Disney ever chooses to build another park is ultimately a business decision. But if and when that decision is made, the opportunity is clear: to build a park that doesn’t need fixing — one that can evolve for decades without being reworked, retconned, or compromised.

A park Disney would only ever need to build once.

Where would you like Disney to build the fifth park? What design principles would you like to see in a new park? Let me know in the comments.